SAMPLE IN ENGLISH

Sigrún and Friðgeir

by Sigrún Pálsdóttir

Translation Sample by Lytton Smith (lyttonsmith@gmail.com)

from Chapter One

The First Happy Time got underway in the late summer of 1940 and lasted through to Fall, far out in the ocean, scores of meters beneath the water’s surface; inside narrow, damp iron hulls where the air smelled of old sweat and diesel fuel; in the minds of German submariners enduring weeks on board ship, part of the longest and most uncertain battle of World War II—the Battle of the Atlantic.

It all started with the occupation of France in the spring. The coastline from Norway all the way south to Spain had by and large fallen under German control; this paved the way for greater access to Atlantic waters belonging to the Allies. However, the German submarine fleet numbered only about fifty ships, not counting Italian reinforcements, and so it was imperative to step up production: the aim was to manufacture twenty-five boats per month, towards a total of three hundred U-boats. A directive was issued, ordering that all ships going to and from the UK, armed or unarmed, were to be sunk without warning—although, in practice, it generally suited the Germans to attack merchant ships carrying military commodities rather than ships that were battle-ready. Like a pack of wolves trapping prey at night, they targeted large, slow-moving Ally convoys. And so incisive was this approach that in one night of madness a squadron of submarines sank a caravan of twenty ships, helped from the air by the Luftwaffe. The bulk of the German airfleet, however, is occupied over land; the Battle of Britain is at its height and bombs rain down over industrial and residential areas of British cities. Night after night, everything is a blaze of fire. But come morning, people creep up out of their holes, more or less like zombies, urged by their charismatic leaders to persevere, to stay alive, in this flaming hell. They are men, women, children—those children not among the millions sent away for refuge, moved from cities and towns to rural areas, constantly hurried and hastened. They are alone, separated from their parents, who gave them away to spare them from horrors and save them from death, even if it meant a long journey into the ash-colored sea.

In late August, three hundred and twenty children, together with their chaperones, need to be rescued from the water after a U-60 torpedo strike on the Dutch liner Voledam several hundred nautical miles north of Ireland. The ship is part of a large caravan bound for Canada. A few days later, some of the same children board the City of Bernares, again headed towards Canada. But it all happens again: this time, the U-48 strikes them. Of the ninety children on board, seventy-seven die in the ocean in their pajamas and vests. It is just after midnight on September 18, and they are roughly four hundred nautical miles west of Scotland.

Sigrún Briem is west of this. A fair way west, away from the conflict zone. She’s sailing under a neutral flag, not that this guarantees her safety: in German minds, Iceland is ruled by an enemy power, and aboard the MS Dettifoss, sailing all on its own from Reykjavík to New York, the sea’s calmness feels suspicious and cold the whole time the ship tracks the coast of Greenland, reaches Labrador, goes through Belle-Isle Strait, and sets course for New York. Then, only then, can Sigrún sit on a deck chair under an awning and read a book. The temperature is about twenty-seven degrees; when she puts down the book, rises from her chair, and walks onto the open deck under the sun, it’s like she’s entered a strange, new place. The heat. She’s never felt such heat before. She sits down again in a sun lounger, leans back on its faded material; she draws a deep breath and places her large, strong hands flat against her lower abdomen. And she lies motionless that way for quite some time, slowly moving southwest, at about eleven nautical miles per hour.

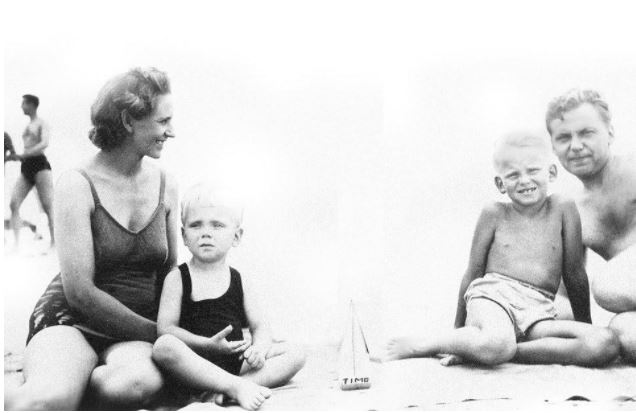

Southwest: the United States of America, the safest place on the planet at this moment, where she intends to study for an advanced degree in medicine, venturing into a new and tangled world as a foreigner, as a wife, as a mother making sacrifices, like many mothers of young children during this war, in the name of common sense and prudence, albeit that Sigrún herself has created the circumstances requiring a sacrifice. In such a tricky situation, emotions have to be handled practically—and yet everything is ultimately founded upon an innocent optimism, unable to know this war’s plots. The unknown offers an enduring hope: that all will continue on its right course. But such a frame of mind can easily be disturbed, and in her half-awake state under the burning sun, on top of the rough and cold ocean surface, Sigrún experiences a sensation one occasionally feels between sleep and waking: life frees itself from it’s previously logical associations, and everything becomes a jumble until nothing remains but the bittersweet knowledge that her firstborn is becoming a person with his own character. Óli Hilmar is but three years old, and when she squeezed him to herself two weeks ago in Reykjavík, from where he set off west to Djúpavík, at Strandir, she knew that the boy was not just saying goodbye to his mother, but to a part of his life that will have vanished from his memory when they next meet. His face was pressed into the safety of her clavicle, his pale crown under her lips as she whispered, certainly, “soon.” First, she would have to talk to the “big man” in America. Then she suddenly turned her head to one side and promised him some red shoes, speaking right into his little ear.

If she is awake right now, her eyes are closed and under her eyelids she’s travelling deep into Reykjarfjörður, where her white-haired tyke trips on the slope at the foot of Háafell. He’s wearing a blue sweater beneath thick bib overalls. His cloth shoes have buckles on. He heads up the hill; a little ways behind him follow a woman and a man. When the woman sits down on a rock, she turns her back to him. She’s wearing a floral dress with a hairband that resembles a scarf when she looks straight ahead; on her nose are round, white sunglasses. She is Ragnheiður Hansen and she stretches her arms back when the boy comes running up behind her, holds him tight by his palms as he leans his body against her back. A snap. The husband—in a thick sweater and waders, and likewise wearing sunglasses—is standing downslope. Guðmundur Guðjónsson, the architect, designer and manager of the new herring factory in Djúpavík, puts his camera strap back over his shoulder and reaches a hand towards Óli. And together, the three of them continue up the hill away from the cluster of houses on the east side of the plant.

They have sailed for nine days and now approached the Manhattan sky, from where a ray of sunlight falls on dozens of brand new, gleaming skyscrapers. The image which confronted the arriving ship had overwhelmed many arriving passengers. The rumors of historical wonders that had been whispered throughout Europe became a reality before their eyes: the RCA in Rockefeller Square, the Chrysler on Lexington Avenue; the tallest building in the world, the Empire State on Fifth Avenue. Most of these buildings had been built in the boom of the Twenties when New York turned into a global financial center and the city earned its international reputation. The citizens madly vied with another in their artistic pursuits, spurred on by bohemian communities in Greenwich Village and among African-Americans in Harlem. Everything was driven by capital belonging to rich white men who shaped the era’s mass culture. Great power lay in the air, but so did longing: people seemed consumed by progress, by thoughts of growth, profit, fame and fortune. In all walks of life the goal was to find the bright star, and one that shone brightest of all was in the media and popular entertainments of the Broadway theaters, where electric lights captivated the masses with all the colors of the rainbow, rolling and flowing, back and forth, up and down, circles and ovals. European cities had nothing like this. Enthusiasm abounded; indeed, the clearest symbol of this ceaseless sprint – the Empire State Building – rose after the Crash had shattered things, as though glory needed to scale new heights to restore what had fallen to the ground from up above.

What’s more, the Crash had been worse in New York than anywhere else in the world. A third of able-bodied men were out of work: men in suits stood on line for food. Many people lost their houses; some people starved, even though a crowd of soup kitchens and shanty-towns had sprung up here and there around the city, including in Central Park. And as the financial abyss facing the city deepened in the early days of the Crash, riots often broke out.

But the steel and the concrete persisted, even if largely deserted, and the tangible creations unleashed by the Twenties’ economic growth are still in evidence when the Dettifoss sails into Hudson Bay on September 2, 1940, headed for the harbor where cargo ships bring those fleeing to the country from war-torn Europe, then fill their holds with goods for the Allies’ war effort. The city, with about seven and a half million inhabitants, is at this time at a turning point in its history, under the stewardship of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. What else could it be? La Guardia, the little flower who couldn’t be more than four-and-a-half feet tall, had overseen significant expansion in recent years; in part by eking money out of the Federal government through President Roosevelt’s New Deal, he’d managed to bring it out of its crisis. Along with Robert Moses, New York City’s master builder, he’d worked to stem road traffic by extending the subway system, and he’d launched transportation projects that forever altered the face of the city. The grandest of these projects was the so-called Triborough Bridge connecting Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx. La Guardia’s final touch, though, is the great World’s Fair; in its pavilions, dozens of countries show off the very best in global manufacture and ideas. In the Icelandic pavilion, a statue of Leif the Lucky and the first white mother in America sit alongside images of Icelandic nature, industry and construction. La Guardia addresse the two hundred Icelanders who were present at the opening and sent greetings—no doubt after consulting with Vilhjálmur Þór, the Secretary of the Icelandic exhibition—from New York City to “the greatest country in the world.” Greetings to a nation which had succeeded where others hadn’t by eradicating poverty and the lack of medical care; a nation that had the courage to live its life without a military defense force. Then he headed out the back door of the pavilion, right past Þorfinnur karlsefni’s statue standing guard.

Meanwhile, at the forefront of the future lay U.S. companies with set ideas of a streamlined, chromium world and, what’s more, plans to release the world’s housewives from their servitude of cookery and domestic chores. General Motors funded an exhibition entitled Futurama, showing the U.S. city in 1960, with the entire organization intrinsically reliant on private cars. And the so-called Democracity, a giant three-dimensional model of a city from the distant future of the year 2039 displayed a scattered metropolis with a sophisticated system of freeways. President Roosevelt opened the World’s Fair, followed by Albert Einstein, one of the European Jews who had fled the European mainland after the Nazi takeover, and who had been hosted by U.S. universities; he talked about cosmic rays. Behind this exhibition in New York in the spring of 1939 lay the idea that in the world of the future nations would live in peace and harmony. That mood soon passed: in the days after the opening of the exhibition the atmosphere gradually changed. Many German-occupied nations closed their pavilions, and it soon became clear that the U.S.’s global role would differ from what the Fair had supposed. Although the war was still distant from most Americans’ minds, many suspected a less beautiful future was around the corner—especially those who had fled Hitler’s Europe, including those experimenting with nuclear fission at Columbia University. Instrumental to this project was the Italian Nobel Laureate Enrico Fermi, who’d fled his homeland at the beginning of the year with his Jewish wife, and the Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard. The latter, together with his colleagues in the U.S., drafted a letter to President Roosevelt, urging him to fund research in this area because the Germans likewise had Fermi’s knowledge, and that knowledge could, in the near future, potentially lead to the construction of an unprecedented and enormously powerful bomb. The Hungarians got the speaker from the World’s Fair, Albert Einstein, to sign the letter, and another refugee Russian Jew, Alexander Sachs of Lehman Brothers, to deliver it to the President in person. In the meantime, the Germans had invaded Poland; when Roosevelt finally received the letter in October, things began to move at speed. The Manhattan Project was headquartered in a twenty-eight-story tower at 270 Broadway, next to the Tweed Courthouse, and quickly spread out across the United States and beyond; it had about one hundred and thirty thousand employees and almost unlimited access to public funds. “Nicholas Baker,” a.k.a. the Danish Nobel Laureate Niels Bohr—also fleeing the Germans—managed the Research Programme in the UK; in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, work would in time begin on the production of enriched uranium; and at the top secret test site in Los Alamos, New Mexico, under the direction of Robert Oppenheimer, many of the key scientists in the world will come together for the purpose of splitting the nucleus of this elusive element, releasing the furtive energy of a chain reaction that ultimately, whether they like it or not, will cast the War conclusively into history.

from Chapter Fifteen

On Thursday, November 9, 1944, the Goðafoss is approaching land, nearing the southern coast of Iceland. Reykjanes lies ahead. Hereabouts, the maritime conditions are often poor, especially when the course of the day has given rise to a substantial wind. This evening a huge storm has arrived with intermittent snow flurries. At two o’clock in the morning, the ship is about twenty-five nautical miles away from Reykjanes. The wind increases to ten on the Beaufort scale and the sea swells. It’s really quite the winter storm; crazy weather. The ship rolls with a vengeance and is washed with sea.

If anyone is worried about submarines – perhaps quartermaster Arnar Örlygur, who’s inside the pantry, trying to shake the significance of tomorrow’s date from his head as he prepares a midnight snack for the night watch – this is all good news. Visibility, however, has worsened enough that the convoy of ships cannot safely make for Reykjanes. The captain decides, therefore, to change direction and turn the ship into the wind, holding course and stopping the convoy. The signalman relays this to the other ships. It’s now about four a.m. and some of the ships still head on their course towards Reykjanes; in all likelihood, they can’t see any of the light signals through the blizzard.

Come seven a.m., it’s still blowing vigorously. The temperature is above freezing, just, but bitter cold. Colder still is the morning light that illuminates the gray iron and the hoarfrost on the gray sea that crashes into the sky at the horizon. But visibility is improving and on the bridge the men can now make out that only three other ships have stayed with the group during the night: a Danish steamer, Ulla, and trawlers equipped with depth charges, the Home Guard and the Northern Reward, which are now sailing with the Goðafoss in the direction of Garðskagi and in towards Faxaflói. There’s a feeling of relief at being able to continue; inside the kitchen, turkey and other gourmet food is cooking in the oven. It is the last meal of the crossing, a traditionally generous lunch.

As the clock reaches twelve midday and dining is about to start, the men on the bridge catch sight of billowing smoke out in the ocean: a ship burning about one nautical mile off. The Goðafoss is headed towards the ship, but when she turns towards Garðskagi the crew spot two lifeboats in the sea, close by. The captain of the Goðafoss realizes immediately that a ship has caught fire, and that it must be the oil ship Shirvan, which had continued its journey during the night and is now about to enter Faxaflói. The lifeboats are headed in the same direction as the Goðafoss; one has a motor and is nearing land. The ship itself lies level on the ocean; there are no signs that it is sinking. Given this, it seems unlikely that the fire on the ship was the result of a torpedo attack; that, at least, is the conclusion of Sigurður, captain of the Goðafoss. He thinks about Sigrún and Friðgeir, and the favourable opportunity the Goðafoss has for rescuing and treating these men if any are badly injured. Nothing suggests that such a rescue will endanger or compromise the Goðafoss. Not now.

The ship is halted and all the crew not on duty are called outside to assemble at lifeboat #1. In lifejackets. Sigrún and Friðgeir are inside the dining hall sitting down at the table with the other passengers when the captain informs them what is happening. People stare out the portholes; some go out into the cold to watch but are driven right back in again. The lifeboat approaches the Goðafoss. Dining has all gone to pot: some of the passengers have headed back out on the deck, some have put on life jackets—an air of uncertainty and misrule is in the air. The attendant, Jakob, had run down to the cabins to fetch Agnar, who was shaving for the celebratory meal and for the homecoming. Agnar had then come running up on deck to be confronted by a terrible sight.

It hasn’t proved possible to lower a lifeboat down into the churning sea, so two of the crew are slowly winched down to the British boat in a net and from there they hoist up nineteen shipwrecked sailors covered in oil and badly burned. One by one, they are drawn up and taken directly to the smoking lounge on the upper boat deck. There, Sigrún and Friðgeir wait with all the medical equipment available on board ship. Sigríður Þormar and Áslaug are with them and intend to assist, but it soon becomes clear that it’s better for Áslaug to take the boys and Sigríður to take baby Sigrún. Best to keep the children away from this. The adults find it hard enough to watch, so badly have the castaways fared. All the same, it’s not necessary to transfer all of them into the smoking lounge; some have escaped with bruises, like the First Mate, who is now standing on the deck talking to Captain Sigurður.

The castaways are all on board ship by about twenty minutes to one. The Goðafoss is ready to continue on her journey. A fire needs to be set in the heating chamber, with great haste to stoke and to feed more coals. High expectations intensify on the bridge when the Goðafoss turns its prow towards Esja, the custom for navigating in towards Gardskaga.

The first mate from the Shirvan is still conversing with Captain Sigurður. They have gone out onto the bridge platform and are deliberating what happened. The former felt certain that torpedoes had been fired at the ship, that it had come under attack. But now he is not so sure, maybe because Sigurður scoffs at him and is highly sceptical: a submarine, in the waters of Faxaflóa? Very doubtful. More likely, the Shirvan sailed into a minefield. Nevertheless, he decides to send information about possible torpedo attacks to the escort vessels, although no special measures are taken on board the Goðafoss.

But the words of the British first mate hang in the air now they’ve been spoken, stalking from one crew member to another and into the dining room and finally into the smoking lounge. The passengers do their best to react nonchalantly: the closeness of the ship to land makes the news hardly credible. “Damn nonsense,” the people say, and try to stick to their plans, eating turkey in the dining room even while, above them in the smoking lounge, the moaning survivors of the wreck are being nursed through their pain. Some are about to lose consciousness and are in such bad shape that it seems amazing their bodies hold together at all. That some of them are clinging to life is astonishing. Sigrún and Friðgeir try to go confidently about their work. In the first aid cases are medicines and bandages. But the worst of the burns are beyond binding. Someone needs to go down to the kitchen and get some potato flour to treat the most serious lacerations and dry them—like the wounds of the fifteen-year-old cabin boy, who lies on the floor between the leather-upholstered stalls. A twenty gallon pot of boiling water had been upended over him. How did it happen? An explosion? Mines, torpedoes? Keep going; bind wounds. Why had Sigrún decided to become a doctor? Did she ever know? Then Friðgeir calls out, asking for a knife. Agnar is down below and comes up from the pantry with one. As he extends the knife, Friðgeir is putting a bandage on a man’s face. On what’s left of it. The bones of the face protrude from the burned, stretched skin. Friðgeir puts gauze over the man’s eyes. The eyes? They are the ruins of eyes. All around men lie, some in just pants and singlets. They need clothes. Where are the clothes? someone asks Eymundur, the first mate, as Sigrún stands up and heads towards the door. Had she heard her baby cry from below when Agnar came up with the knife? And remembered that she hadn’t fed her daughter yet? She goes quickly and confidently down the stairs and into the dining room; at the same time, Sigurður the deckhand is coming up the outside stairs into the smoking room to offer his assistance. Inside the dining room, Sigrún takes her daughter from Sigríður Þormar’s arms, asking her to go down to the kitchen and heat a bottle. But she needs to head straight back to the smoking room, so she decides to bring her daughter along.

As she walks out of the dining room, into the hall and up the stairs, Áslaug, Óli and Sverrir are coming in from the cold, through the outside door that leads directly into the corridor by the refectory. It’s no weather for being outside. Óli is toddling along the corridor, perhaps thinking of the dessert that’s yet to be served, but Sverrir is fussing and wants his mother. Áslaug sits him down and tries to calm him. She’s wearing a black coat and the Japanese rain hat on her head, the hat she’d only recently recovered after it had blown off Sigríður Þormar’s head—she’d borrowed it one stormy day, and it had gone out into the blue yonder, so they thought, though it had actually fallen beside some cars down in the hatch. Áslaug doesn’t any longer plan to wear it in Reykjavík, though—wouldn’t people stare at her?

Sigrún enters the smoking lounge through the inside door; Sigurður the deckhand has already left from the other side. The first mate Eymundur has sent him outside to get sweaters and other garments for the poorly provisioned castaways. At this very moment, Captain Sigurður is raising a telescope to his eye; he sees a black flag hoisted aboard one of the escort ships. A submarine close by. At the same moment, Ingólfur the deckhand strikes the ship’s bell. It’s one o’clock; time for the shift change. Sigurður the deckhand is standing in front of lifeboat #1, which sits in place on the upper deck, up on its stand in front of the smoking lounge, on the starboard side. Inside the boat are the clothes he’s meant to fetch, but just as he is about to climb up into it, he looks out to port and sees a white streak in the sea approaching with tremendous speed. Without thinking, he calls with all his strength from the bridge, “Torpedo, torpedo!” With all his strength—right before he is knocked to the deck directly in front of the boat; right before the securely screwed-down radio and receiver are thrown about the armored radio cabin as its walls cave in; Captain Sigurður, along with several of the sailors, falls to the floor of the bridge; a 50 gallon tank of boiling washing water tears away from the wall of the kitchen one deck below, and the stove cleaves in half, clay tiles wrenching from the ground and rushing up into the air as Lára the stewardess, Guðmundur Árnason the chef, Sigurður the cook, and Sigríður Þormar, in a life jacket and carrying little Sigrún’s bottle, are all are thrown up and then down to the floor; chef Guðmundur Finnbogason trips on the doorstep between the storage corridor and the kitchen, a can of fruit cocktail in one hand, dessert for Óli and Sverrir; the floor of the pantry rips in half so that Arnar Örlygur seems to be headed down into the huge, black coal storage; Jakob the attendant and Stefan the cabin boy are flung onto the pantry floor and after them follows food, plates, dishes, knives and other kitchen things; the pantry door swings out into the corridor in front of the dining room where Áslaug has fallen onto Sverrir amid empty cases of oil that have been thrown about. “Torpedo, torpedo!” And Sigrún falls too, her daughter in her arms, onto a leather-upholstered couch inside the smoking lounge directly above all that chaos. And from there to the floor, as the gigantic and unimaginable crashes against the ship’s port side, mid-ships, so that the ship is lifted with a deep, cold, metallic sound din and seems to rise out of the water.

Everything is black darkness. Sigrún is nowhere, or rather some place in between life and history. If she opens her eyes, she no doubt closes them immediately; she loses her grip on the thing she has in her hand when she lifts it up to her forehead to ward off the coming brightness, a defense against the awesome light. A pen falls quietly to a white beach, a small notepad on a faded canvas sun chair, as she turns suddenly to look out from under her hand’s sturdy roof. That’s it. Right at her feet sits Sverrir. He’s in a dark blue bathing suit and he’s sitting at the tide line so that the waves float up under him. In one hand, he holds a shell; with the other, he digs violently down into the sand. Two little girls—also in blue bathing suits—try to catch his attention, which is focused determinedly on grains of sand that fall slowly and sparkling to the ground from his clenched baby fist. Sigrún looks up and over to where Óli has gone out into the sea. He’s got a sailboat and makes it skip on the waves which reach to his waist. He inches his way farther out and doesn’t hear when a car drives along the road above the beach and stops in front of the summer house. Out steps Friðgeir. In his arms, he has a white box marked Lyndell’s Bakery. Since 1886. Sigrún gets up from the sun lounger, gathers Sverrir in her arms, and heads towards the house. Friðgeir has come in and placed the box on the kitchen table. He puts his arms around them. He’s about to whisper something in her ear when Sverrir clambers across, wanting his father, who lifts him up over his head and walks towards the front door with him. Sigrún reaches both hands toward the box on the kitchen table and gently opens it: “Happy 6th Birthday Oli.” She watches through the kitchen window as Óli comes running out of the water towards his father and brother; in her mind, she constructs a sentence for this father about what’s been happening; as he makes a gesture amid his young sons, he calls to her mind another father, her own: an old official, standing at this very moment in a three-piece suit before his bureau, a silver letter knife part way through the layers of tape covering the re-sealed envelope, about to begin reading sentences from his son-in-law the U.S. authorities seem to have already read: “They’re terribly brave and so much fun that I can’t do anything but orbit around them after I come home each day, right up until they go to sleep.”

When the ship slams back down into the sea it lists forty degrees to starboard. Its prow vibrates jarringly and the ship rolls under the blow. Sigrún stands up and somehow staggers through the darkness with her daughter in her arms, stepping over the men lying on the floor, out of the smoking lounge, out onto the starboard deck. Suddenly Friðgeir is beside her. Neither of them has a life-jacket. There’s a fresh gale, about eighteen meters per second. A lot of sea washes over the deck below. Everything smokes and steams with a hissing hum, but past this haze one can see parts of the deck have been torn up; a large area of the port side is missing, and out of the ship’s side shoots all kinds of junk, bags of wheat, boxes. A sizeable wound has appeared below the ship’s house, inside which someone is supporting Sigríður Þormar away from the boiling steam. Guðmundur is still laying half-in, half-out of the kitchen and Arnar Örlygur, black dust covering his white chef’s uniform, hangs in the pantry threshold, his legs dangling down into the coal storage. Within the pantry, Jakob and Stefan crawl up the slope to where the door out to the corridor in front of the dining hall still stands ajar. And from the corridor bursts the sound of children crying. Áslaug totters to her feet with Halldór Sigurðsson’s help, as he and the other passengers come out of the dining room; she heads straight out on deck with Sverrir in her arms. She goes up the stairs and out to where Friðgeir is setting a life jacket on Óli, who has come running out of the refectory along with the others.

Someone calls out from the smoke, “Women and children first” and the English signalman puts Sverrir in a life jacket; the boy cries so much that Friðgeir takes him out of Áslaug’s arms. A crane lies on the floor, pieces of wood all around; the aftermast has broken and fallen down on the starboard side, so that it’s now on top of the cars which had been battened down in a caravan, only to be thrown up by the impact: they lie in a heap near the gunwale. Old Grey is there, its wheels up. The Packard is on the other side of the hatch near the prow; it has barely budged in its case.

The lifeboats on the port side are both shattered and the fastenings on the hindmost starboard lifeboat have fallen apart; it hangs down at one end and so can’t be launched. Several crew members are trying to get outside from the main deck mess. Everything is broken and the door has warped in its frame so that it’s not possible to open it outward, but a gap has appeared in the panelling and some of those inside the mess try to squeeze out through it.

Captain Sigurður has come to; he stands out on the deck near lifeboat #1, the only boat left whole after the attack, and issues commands. They little resemble the lifeboat drills in a Scottish port. Guðmundur Guðlaugsson the engineer comes up the stairs with Sigríður Þormar in his arms. Under the life jacket her thin silk blouse is wet, as is her skirt. After them come Lára and the head cook, Sigurður. They are both horribly burned, Sigurður all the worse, but there is nothing to be done for him and nothing either for the British First Mate who is wandering about on deck, bandaged and almost without a face. Within the fumes and the smoke, shouting and calling can be heard, yet there is a strange calm over everything; the crew carry out their duties and the passengers follow as if in a trance.

The sailors untie the life-rafts and three of them are put to sea. Some of the sailors are already beginning to throw themselves into the sea after the rafts. It’s soon apparent that not everyone will fit into the only intact lifeboat, which the crew are now, at the captain’s order, trying to release. A few stand in the boat and work like mad at the davits so they can ease the boat down. Others help the passengers in. Ellen Downey stands at the front of the boat with little William. Sigrún has her daughter, Friðgeir has Sverrir, and Óli and Áslaug are not far off. Sigríður Þormar is beside them, supported by the railing at the front of the boat, wearing Ingólf the deckhand’s coat; he is one of those trying to undo the block and tackle amid the smoke that billows from steam and fire. The deckhands Sigurður and Baldur are in the other end of the boat, trying to free it there. The boat is in constant motion and leans heavily towards the deck.

Suddenly so much sea surges under the boat that Sigurður and the others are thrown back out onto the deck. This does not bode well. Wouldn’t it be better to throw oneself overboard and try to get on to a raft? Perhaps the possibility hangs in the air for a moment and explains what happens next: Sigrún hands the helmsman, Þórir Ólafsson, who is standing beside the life-boat, her daughter. Þórir takes little Sigrún and puts her inside his jacket. No words can be discerned, nor any of the child’s cries heard. Then he and the child vanish behind the smoke and steam. But throwing oneself into the swaying green sea with a child in your arms might not be such a good idea, however, Friðgeir seeks to hand Óli into the boat, to pass him to Ingólfur, who is still trying to untie the first fastening. Every split second matters because the ship is going down and the boat will be of no use if they can’t release it from the side in time. This had often taken time on a level vessel in calm seas, but in this kind of weather, under pressure and with the fate of the passengers at stake, it’s far from an easy task.

Finally Ingólfur manages to free the block and tackle, but the boat is still fixed fast at the other end. It’s like the fastenings have been damaged by the blow from the depth charge; the useless equipment makes the crew all the more nervous at this crucial moment. And once the block and tackle are freed, how to ease the boat down in the conditions? Moving too fast, the boat will break into pieces. It’s like the equipment isn’t right for a sinking ship. The boat can’t go too fast, or else it’ll slam into waves—but not too slowly, or as it approaches, the crests of the waves will fill it with sea. If it isn’t released steadily, carefully, in tandem at both ends, the weight in the boat might get displaced suddenly like a slatted blind and the passengers will fall overboard. Exactly that happened when all those British children ended up in the water in the early autumn of 1940, tipped from their boats in their pajamas, down into the ice-cold sea.

The boat, though, is the sole hope of those who can’t cast themselves overboard and swim to a raft. The butler, Frímann, comes over from inside the boat and takes Óli from Friðgeir’s arms. Then he reaches for Áslaug and Sigrún opposite. Does Sigrún turn her thoughts to her conversation with Doris in New York? Can this reality she faces allow her to look back with regret? Is it even possible for her to think through such thoughts in the few seconds it takes to sit down on the boat’s thwart and embrace Óli as hard as she can with her large, strong hands, looking all the while at Friðgeir, Sverrir crying in his arms, the Goðafoss continuing to lean, its deck split in two, its stern raising ever higher up from the sea and the life-boat tipping sideways at the same time?

The sea comes up on either side like two walls and Friðgeir launches himself into the sea from the deck with with little Sigrún and Sverrir, followed by their mother, thrown from the boat. As soon as that happens, Frímann casts himself overboard and heads to a raft, managing somehow to drag Áslaug with him, because she’s closest to him—but the raft drifts immediately away from the ship and the lifeboat still stuck to it.

And Óli in his coat with his hat on his head—the hat which he’d grabbed as he ran up to the boat deck, and which Ingólfur handed back to him after the wind had blown it off his head down onto the thwart as he waited to get on board—seems in some magical way to have got back onto the ship deck, where he stands motionless at its foremost tip, or what’s left of it, far above sea level. The ship is breaking to pieces in its middle and the stern is pointing up as Sigurður the deckhand grabs the little boy and jumps into the sea, not waiting for the waves to come up to the ship’s side and lessen the drop—as Agnar does, standing and waiting for the right wave—as though he wants to rescue the boy as soon as possible from the death trap the Goðafoss is becoming, on its way down with a powerful suction that will draw every person on board into the depths.

Yet the sea’s cruel face causes many to cling to the ship for dear life, like the person hanging from a rope from the foremast all the way down to the sea, where people are journeying uncontrollably up and down the waves’ valleys, shouting for help as the last two life-rafts are swept farther and farther from the ship, which disappears below the water’s surface, down and into the darkness with a splintering hullabaloo.

Óli goes under with the suction but is able to kick in the depths and gets back to the surface to last just a single merciless moment longer. People try to grab onto whatever they can, to climb up the boat’s keel or swim toward the rafts. Sigrún and Friðgeir are nowhere to be seen; they have vanished into the sea after their children.

What is happening under the surface of this greying, ice-cold ocean? What happens to that reflex, that desperate need the drowning have to get to the ocean surface, to breathe—that bodily reaction Friðgeir had described so well on his final medical exam in early 1938—when a person holds onto her young child or is sure she can reach her child if she only drinks a little more of the sea? How does the material struggle for breath come to an end? Or is it that one’s spirit—the strong wish, so utterly powerless, to keep yourself and your three children afloat in the cold sea—produces so much despair that the body loses control of its respiration? Just how does a person drown with her children?

The Goðafoss is no more. Not even six minutes after the torpedo strikes the ship and the young submariners, long-bearded, red-eyed from insomnia, their heads half-full of the glory of war—something about which they rarely talk—were lifting their hands to slap salty palms and cheer with wound-up euphoria this long-awaited victory after the past week’s defeats and Allied depth charges. Playing background to the celebratory sounds was the constant drone of the engines, and a nagging suspicion that carved the moisture-saturated air: the notion that their own world might soon collapse, that their sacrifices were in vain, that nothing awaited them but fleeing from Faxaflói, then moldy food, clogged toilets, a brief rest in the hole, and finally an excruciating death in iron coffin 300, deep on the depths of the seabed. And what can perfect this miserable world but two life rafts, several hundred meters away, moving further and further away from the people who swim in the sea and hold feebly onto debris, to rescue rings, to all kinds of flotsam junk from a ship which never so much as carried oil for British planes to raze German cities to the ground? An upside-down lifeboat and a young girl hanging to the keel, so exhausted that is not be able to reach out when help finally arrives and slides, dying, into the sea? A baby’s blanket which rides up and down the waves’ troughs? A weak shout for help, a gurgling voice directed towards the crew of the escort vessels which seem determined to follow the rules and return fire before helping people out of the sea? Determined to shed all those depth charges that send the water high into the air with a powerful gush that makes everything vibrate and shake until everyone’s cries have stilled and nothing is left but the waves’ rising and the wind’s whistling. The plash of sound when the sea is bailed from the raft. The tremoring of the people sitting there.

And the darkness below the water’s surface becoming blacker with each word that tries to describe what has taken place underneath.